Capitalising on Player Potential – The Myth of Moneyball in Soccer Part 2

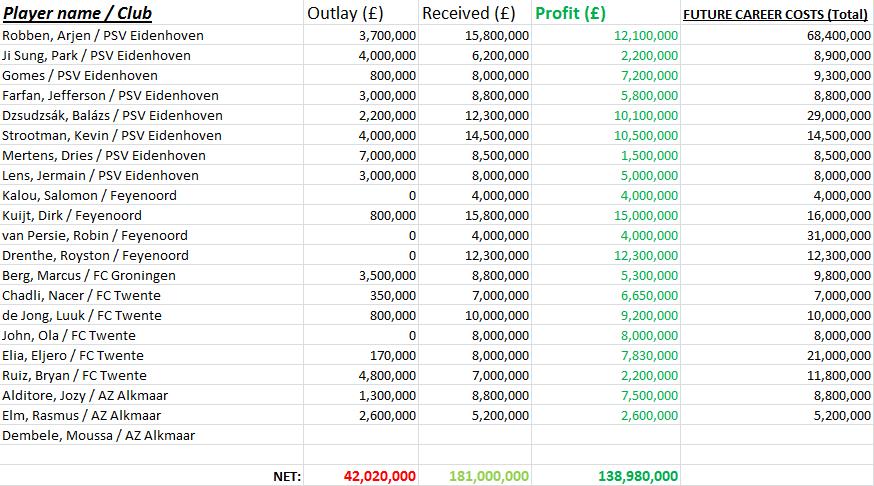

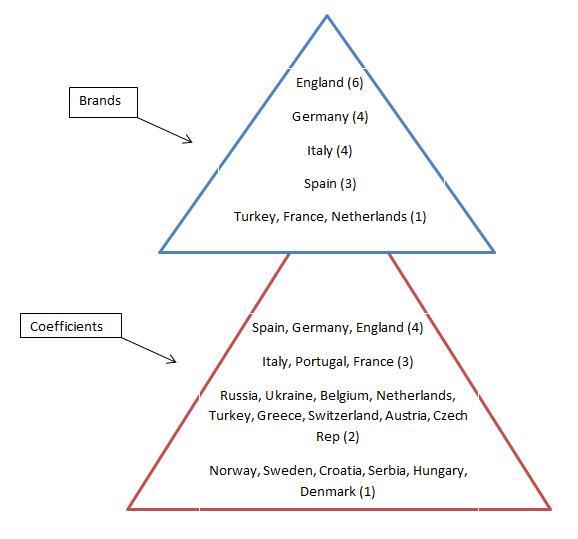

As shown above, when a player is sold to a club he may still be striving and be deemed too good for that club. Because of this, it would be viable for the player to transfer to a more competitive club. Observe the image above and note how the value of several players increases as they move up the league structures. For example, Arjen Robben was arguably worth more than the £15m that Chelsea paid. Another example, which is not seen above, is Nigel de Jong, who has since gone on to be more valuable than the £1m fee that Ajax received. To clarify what is mean by league structures, acknowledge the pyramids below. The above blue pyramid shows data from brandirectory.com regarding the top 20 brands in world soccer As you can see, there aren’t any brands from Portugal, Scandinavia, the Balkans, South America or Asia. In our contemporary game this may offer an inclination as to why players sign for ‘bigger’ clubs, as these clubs have the necessary funds to entice such players. The red pyramid below it highlights the current UEFA Coefficient. The countries at the top of the pyramid are deemed to be elite in European competition. It can be theorised that the higher up the pyramid a teams league is, the more money they can negotiate for their players.

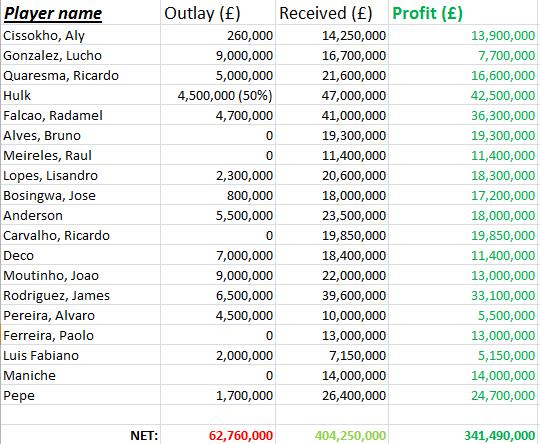

Proof that leagues higher up the red pyramid have a stronger footing in regards to negotiating fees for their potential players can be recognised by reviewing the three charts below. The first chart details the income of Porto in the last ten years (their windfall following successful Champions League campaigns has helped to determine their bargaining power) who have shown magnificent ‘FIPG’ vision under long term owner Jorge Nuno da Costa.

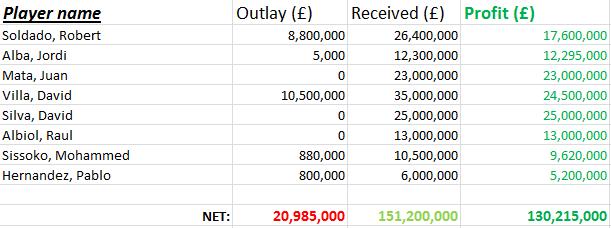

It could be argued that this approach is succinctly belonging to one club, a club who have performed admirably in European competition under the stewardship of Mourinho and Vilas Boas. However, Benfica (seen in the next chart) overcame financial uncertainty towards to end of the 1990′s to gain an enormous profit through investing in potential growth. Their profits can be seen below;

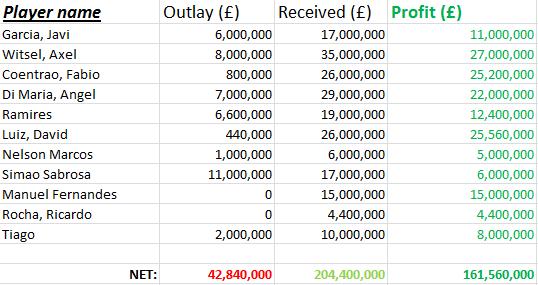

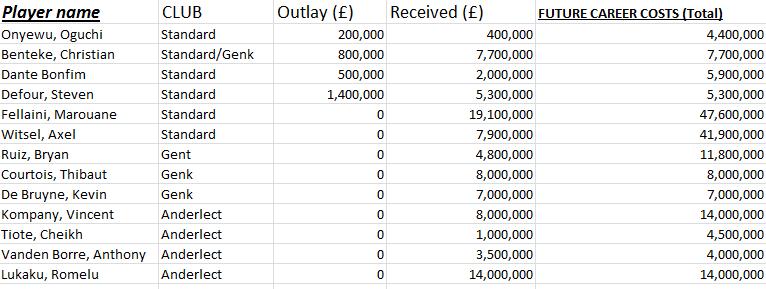

Benfica and Porto have made a combined profit of over £502m in the last decade. To understand that this is due to the strength of the Portuguese league in the coefficient ladder (amongst other factors) one must consider the third table seen below. Belgium is a hotbed of soccer talent, yet the combined income from key transfer sales departing the league in the last decade (forgive me if some players have been overlooked) is around £400m less than the intake of Porto and Benfica combined.

Belgian clubs could not demand a sufficient fee for their assets. When Witsel and Kompany left for foreign shores they were potentially worth a lot more than what Standard and Anderlect received. Readers may be naively labelling the mentioned clubs as ‘selling clubs’, a term used in Britain to malign the inability to hold on to key assets. Whilst several ‘selling clubs’ do exist in world soccer (without shame), FIPG is a separate systematic approach. As the reader is aware, soccer is a constant negotiation. Few players comfortably find their level and prolong their stay. When they do so it is a beautiful thing – Totti and Roma have constantly challenged each other. This is not always the case, for example: Fernando Torres was performing admirably at Liverpool for several years, yet when the club started to decline he became disgruntled as their relationship was not mutually beneficial. More commonly we see the player under-performing and therefore failing to benefit his club. In response, the player is sold.

Valencia can rightly be labelled as a selling club despite starring in one of the worlds ‘top’ leagues. Unfortunately they have amassed great debts in the previous decade, and have therefore been forced into selling their assets. This was not an FIPG approach. Valencia is an example of the variables that affect transfer fees, such as; debt, expiring contracts and the self negotiation of TV and sponsorship deals.

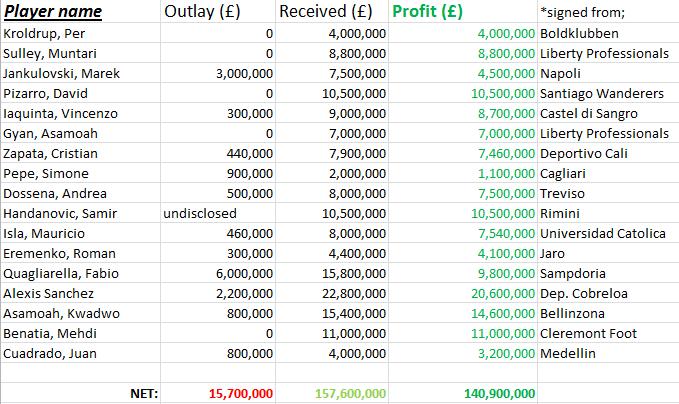

At present, it is vogue for a club to spend within its means. Germany’s Bundeliga has shown the benefit of investing in youth academies. The difference between Schalke, for example, and Ajax, is that Schalke can afford to retain their talented assets. For FIPG to work, it is necessary for clubs to recruit suitable players at their lowest possible cost. A fantastic network of scouts would is a prerequisite for this approach to work. Observe Italian soccer’s shining light, Udinese, and it’s recruitment of unknown young players from obscure teams throughout the world;

Returning to Billy Beane’s baseball statistical recruitment, his philosophy was made soccer flesh by Atletico Mineiro in their successful 2013 Copa Libertadores campaign. By recruiting unwanted ‘has-beens’ such as Diego Tardelli, Josue, Gilberto Silva, Jo and Ronaldinho, manager Alexi Stival over-performed on a small budget. This, was ‘Moneyball’ in the third ‘unwanted talent’ category. On the other hand, it could be argued that these veterans were on large contracts for a Brazilian club of Mineiro’s stature: a gamble which paid off for them. Hopefully this article has differentiated the financial approaches used by soccer clubs from the baseball approach of ‘Moneyball’. It is a common misconception to label a club achieving financial success beyond their means as doing so through a ‘Moneyball’ approach. Hopefully by reading this you can acknowledge the finer processes involved.

Returning to Billy Beane’s baseball statistical recruitment, his philosophy was made soccer flesh by Atletico Mineiro in their successful 2013 Copa Libertadores campaign. By recruiting unwanted ‘has-beens’ such as Diego Tardelli, Josue, Gilberto Silva, Jo and Ronaldinho, manager Alexi Stival over-performed on a small budget. This, was ‘Moneyball’ in the third ‘unwanted talent’ category. On the other hand, it could be argued that these veterans were on large contracts for a Brazilian club of Mineiro’s stature: a gamble which paid off for them. Hopefully this article has differentiated the financial approaches used by soccer clubs from the baseball approach of ‘Moneyball’. It is a common misconception to label a club achieving financial success beyond their means as doing so through a ‘Moneyball’ approach. Hopefully by reading this you can acknowledge the finer processes involved.

Leave a Reply