Capitalising on Player Potential – The Myth of Moneyball in Soccer Part 1

‘‘Moneyball’ is a term which refers to the strategic, analytical approach of recruiting professional baseball players of a competitive standard, despite the recruiting team having poor financial resources: ‘it is a refusal to spend beyond ones means, whilst ensuring that a profit can be made.’ Pioneered by the Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Beane and scribed by Michael Lewis, Moneyball’s success gained fame. It has since been adopted by the majority of baseball teams.

The philosophy of Moneyball has been associated with soccer in an ambiguous manner. For example, a team who works on a tight budget yet manages to sign players and later make a profit on them may be been deemed as achieving ‘Moneyball’ success. It should be highlighted that the key difference between baseball and soccer is the absence of transfer fees in baseball. The Oakland Athletics did not sign players for around £1.5m and later sell them for around £10m, rather they drafted in players who were undervalued by others, yet matched key statistics that Beane and his staff found desirable. Beane, himself founded a link between the two sports: ‘Every business has metrics that correlate to success, it’s just finding them and which ones are the most valuable, and which ones do you invest in, and which ones you get a return on.‘ ‘Moneyball’ has since became an adjective for the philosophy. Nevertheless there can be no doubt that Beane’s words ring true. German clubs have achieved great success recently by investing in their structures, their fans and their academies. Other clubs across the continent have found success through alternative approaches. This article will dissect the key approaches which achieve clubs financial success, all of which are clouded under the blanket term of ‘Moneyball’. These approaches will involve the likewise use of performance software and computerised databases, similar to Beane’s approach. They will also ensure that the investing club achieve success, if not through trophies won, then by capital gained. However, these soccer approaches deserve to be differentiated from the ambiguity of ‘Moneyball’.

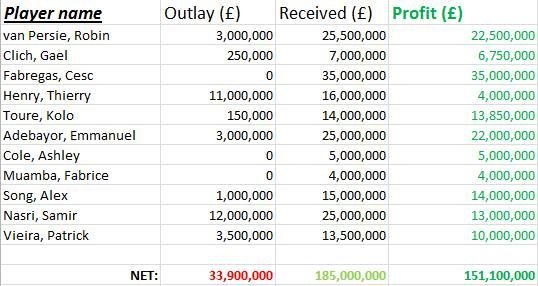

An accurate depiction of the umbrella term in regards to soccer was provided by Simon Kuper (2011) who recalls how Arsene Wenger discovered a replacement for Patrick Vieira by searching through databases’ for midfield destroyers who ‘covered the most ground per match.’ The search, as Kuper tells, produced a rookie name in Mathieu Flamini – obscure in the sense that Flamini was a fresh talent, not largely sought after on the continent. When Wenger discovered that Flamini could also play a little, he chose to sign him, and cashed in on Vieira’s statistical decline. Speaking about Wenger, Beane told Kuper: ‘If you have less money than your competitors then you can’t do things in the way they do, otherwise you are destined to fail – If Arsenal, Man Utd and Chelsea want a striker then Arsenal will get the third-best striker.‘ This explains why Wenger, the economics graduate from the University of Strasbourg, would rather shovel for gold and sign potential. More often than not it has worked (see below). Wenger has gained success with this approach throughout the course of his career. At Monaco he courted a young striker based in Liberia called Weah. Later his, and Arsenal’s, financial success has came from the ability to sell at the right time. Henry (29) left for £16m, Vieira (29) for £14m, Petit (29) for £7m and Marc Overmars (27) for £25m. As Kuper points out, none of these players did quite as well after he sold them. It is important to remember that none of this is moneyball. The Oakland A’s did not sell players. But for Wenger, the ability to sign young and sell at the right time has generated a lot of capital for his club. The chart below shows the obscurity of signings such as Kolo Toure and Gael Clichy who had the potential to be stars. It is called FIPG – financial investment into potential growth. This, is the first approach under the moneyball umbrella. All of the below signings had potential to develop into valuable assets, and they did so. Ponder what Arsenal would have achieved had Wenger persuaded a young Zlatan from Malmo, a boy called Cristiano from Sporting, a young Le Mans striker called Drogba, and Kolo’s brother Yaya, all to sign, too.

*van Persie’s initial fee varies according to source. Most fees taken from transfermarkt*

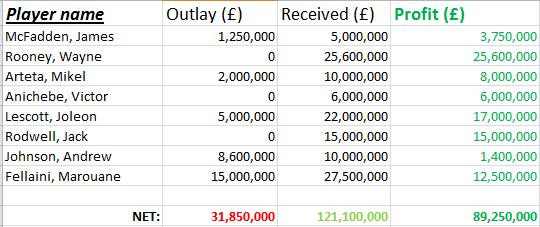

Billy Beane found a light in the unwanted. He understood that the financial demands of a castaway professional would be a lot less than that of a man whose star was at its highest. Not many teams in soccer can afford to sign a player who is at the pinnacle of his career (more on this later), yet if there is one manager in soccer who can relate to Beane and his approach, it is David Moyes. While as Everton manager, Moyes charged his staff with the task of analysing databases for players who were strong, resilient and cheap. It took real vision to see that Steven Pienaar was not as troublesome as other clubs believed. He was a talented soccer player who was pivotal to Everton’s FA Cup run of 2009, he came with European and International experience, and best of all for Moyes cost only £2,000,000. That Everton team of 2009 was a beautiful concoction of the three financial approaches; FIPG (players on their way up, products of intensive scouting), unwanted talent (transfer listed pro’s who had a lot left to give; this article will avoid talking about such players for the most part) and academy graduates (who are often attractive for investors).

- Howard – unwanted

- Hibbert – academy

- Yobo – hard to categorise, had potential and was product of intensive scouting

- Lescott – FIPG

- Baines – FIPG

- Osman – academy

- Neville – unwanted

- Pienaar – unwanted

- Cahill – FIPG

- Fellaini – FIPG

- Saha – unwanted

Moyes worked on the old cliché of a shoe-strike budget. Regardless of this, he over performed through a meticulous analysis of potential signings. Consistently, Everton outshone ‘richer’ clubs in the transfer market. One of the fundamental aspects of Moyes tenure was the utilising of the academy at Everton. Merseyside, and indeed the North-West of England is a hotbed of talent. Hibbert and Osman found their level in the first team. Rooney strived, as did Rodwell, both of whom received massive transfers which benefited all parties. It seems likely that the latest graduate, Ross Barkley, will follow in their footsteps.

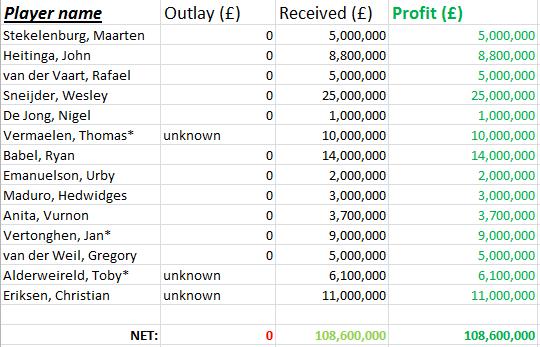

With this in mind it becomes noticeable that a soccer club can base its financial existence on the quality of its academy. Ajax of Amsterdam are a club with a blueprint based around the success of its graduate system. The manager, Frank de Boer, is appreciative of this and concedes that key players promoted from within are always likely to leave the club. With a combination of the Cruijffianen and Van Gaalisten schools of thought – individual and collectivism intertwined – De Boer has lain the foundations of a system whereby the whole is greater than its sums. He created roles for every position which are basic enough to constitute towards the team as a whole. Because of this, when an Eriksen leaves, a Klaassen can step up. Despite being a position of strength whereby Ajax can entice the ‘better’ teenage Dutch players to their academy, if you consider the club on a European scale they are magnificently self-sufficient. They are green-power; in fact, 30% of the Eredivisie came from Ajax’s academy. When they do sell a player, if they fail to promote a youth candidate in his place, they reinvest. Alongside the sales seen below, there have been FIPG signings who were on their way to more ‘affording’ clubs: Luis Suarez, Klaas-Jan Huntelaar, Zlaatan Ibrahimovic and Christian Chivu.

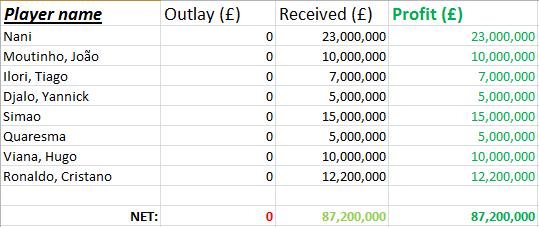

People will ponder whether a British club could implement a similar approach, but several variables must be considered; Ajax play at a lower standard which is less competitive and allows for greater development. For Premier League clubs it is too dangerous to gamble on youth. Think of other strong academies throughout the world and you will find that their youngsters are also nurtured in a less competitive environment; Sporting Lisbon play in a league weaker than the EPL, hence why Tiago Ilori was on the fringes of the first team for several years in Lisbon but is now in the U21′s for Liverpool. People may point towards Barcelona and Bayern Munich, the two best sides in the world who contain mostly academy graduates, yet both of these clubs have ‘B teams’ to harness growth until the required standard is reached. Ajax and Sporting, though, provide validity towards an academy based approach in the pursuit of capital.

As mentioned earlier, FIPG is the financial investment into potential growth. Think of it as an ability to gain capital by purchasing players who are good enough for the short term, who will progress into assets in the medium term, who will be sold and reinvested in the long term. For this to fall under the category of a ‘Moneyball’ approach, the club must avoid spending beyond their means.

The competitiveness of the league has been mentioned as a key aspect when developing players (the league must be accommodating to development), however, and more importantly, the team who hold the asset should be involved in European competition to have enough financial clout to negotiate transfers. According to Deloitte, the English Premier League generates five times more for its clubs than the Eredivisie: 2,500,000,000 / 420,000,000, therefore it is not a case of whether a player will leave the Netherlands or not, more so it is a case of ‘how much?’

Leave a Reply